Co-Conspirators: Artist and Collector

The Making Of A Collection

By Sue Scott

In late May 2004, Jim Cottrell and I visited Malcolm Morley and his wife Lida at his studio in Brookhaven, Long Island. I had a specific project to discuss with Morley, and Jim came along to catch up with a favorite artist. Morley greeted us at the door of his home, a converted church located at the edge of town. On our way into the studio, we passed a beautiful antique cabinet packed with the objects and models found in Morley’s paintings: tin soldiers, wooden boats, castles, knights and countless “three-dimensional watercolors” of ships and planes, hand-constructed from watercolor paper and then meticulously painted, often in a tromp l’oeil fashion. One of the larger models, the historic “Santa Maria,” is a primary image in Morley’s painting Santa Maria with Sopwith Camel Wing (1996), in the Cottrell-Lovett collection.

Jim and I descended upon every inch of the studio, and the next two hours were marked by energetic exchanges as Morley showed us current paintings, new prints and pictures of previous work we had never seen. In mid-afternoon, we finally broke for lunch at a local restaurant, and then returned to the studio where inevitably Jim, the obsessive collector, purchased two prints we’d seen earlier. As Lida and I made some arrangements in the other room, Jim, who is an anesthesiologist, discussed science and the brain with the artist, interests they had shared over the many years they had known each other.

That same day, Joe Lovett flew to Buffalo, New York, for the closing of the exhibition The Domain of Perfect Affection, featuring the work of Patricia Cronin, an artist and good friends of the collectors. Joe, a film director and producer, attended the show at the University of Buffalo to film an episode for “Gallery,” a subscription series for Voom, which is a high-definition cable service. The previous weekend, Jim, Joe, and I visited Deborah Kass in her studio in Brooklyn to film an episode for the same series. Jim and Joe collect Kass’ work in-depth and along with interviewing the artist, Joe wanted to film Jim’s reaction to Kass’ newest series of word paintings, which she’d been working on for several years.

I relay these three vignettes because I believe they exemplify Jim and Joe’s approach to collecting art. They posses an obsessive desire to see and know everything about the artist they are interested in and after making that connection, to provide ongoing support. “Once I find someone I really like,” Jim says, “I continue to acquire their work. Many of the artists we met and whose work I bought in the seventies and eighties, we still collect.”

Both men believe it is important to look at many works by the same artist, to read about the artists and to talk with them, if possible. Their mantra on collecting is: Learn as much as you can, in any way possible. Over the nearly 30 years they have been collecting, they have not only become friendly with a number of artists and developed deep friendships with others, they have created a life in art that occupies most of their waking hours outside of work.

In reflecting on how the collection began, Joe notes, “The work I originally collected was given to me by artist friends. I never had a desire to own grand or expensive works. I am just as happy to see art in a museum as on my own walls. But one day, Jim said to me, ‘If we don’t buy it, how will the artist survive?’ “

In a world where an artist’s income can be drastically affected from year to year by the whims of fashion, patronage is an essential, but less obvious, role played by collectors such as Jim and Joe. Artist Barton Benes, whom Joe has known since 1966, concurs. “Jim and Joe buy seriously and regularly. And as my work changes or I move in new directions, they grow with me. They’re willing to take the leap and go to this new place with me. They’ve stuck with me, always. They’re true.” Over the years, Benes has made works using currency and about AIDS. He has created “mini-museums” that deal with topics such as murder or food. And, in the final stages of production is a film on Benes’ art titled “No Secrets,” which Joe is producing.

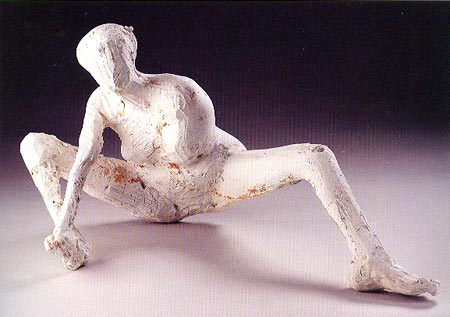

The two collectors do not often commission works, but several years ago they commissioned Donald Baechler to make a fountain for their backyard. Although the sculpture is not a focal point of their collection, another fine example is Seated Female Figure (1961) by Manuel Neri, which has the same expressive qualities and tactile surfaces that defines the aesthetic of the collectors.

Jim and Joe’s approach to collecting differs from other collectors in many ways. Some collectors prefer not to meet the artist, believing the painting or object must stand on its own. Others collect one example from many artists. Some chase trends or “update” their collection over the years to reflect the changing times or their changing taste. For Jim and Joe, collecting art is a continuum linked together by experience and friendship. Today their collection numbers nearly 400 pieces and includes works by many major international artists.

Joe readily admits that for the most part collecting art is essentially Jim’s passion. And he hasn’t always loved the direction it’s taken. In fact, he told me a few friends refer to it as the “in-spite-of-Joe” collection. “Sometimes, Jim brings home something I really don’t like,” he says, “but he never brings home anything that is dull. It is all work you can engage with. They all have stories. I know some people move paintings around because they are bored with them. That is never the case with us. Jim moves them to allow us to see one that has been in storage.”

This is a collection that starts with, and is sustained by, the act of looking. “The image, or composition, has to attract me,” says Jim, “but after that initial jolt of energy, you have to go somewhere with it. That is when it becomes important to understand what the artists are about, the journey they are on and what they are doing with their lives. But the image has to be there first. I have to like what I’m looking at.”

An offshoot of being involved in the lives of the artists one collects is the influence that artists inevitably have on that collection. This is the case with Roland Flexner, an artist represented in-depth in the Cottrell-Lovett collection, and the person responsible for introducing Jim and Joe to much of the art and many of the artists in their collection. Flexner and Jim met in 1982 through Flexner’s wife Sue Williams, a film producer with whom Joe worked. After Jim’s first visit to Flexner’s studio, he purchased the large painting Untitled (standing figure throwing light) (1985).

“I thought it was very mysterious,” Jim says, “and the technique was incredible. The more I learned about Flexner’s unique blending of oil painting and gilding on canvas, the more I was intrigued.” Jim continues to collect many of Flexner’s works, including numerous large paintings and several drawings. Initially, he was attracted by the exotic flavor of the work and knowing Flexner was from Nice, he associated rich color and flatness of the paintings with the work of Henri Matisse. As with many of the artists whom Jim befriends, the two quickly found other, non-art related points of connection. For instance, Flexner’s uncle (a composite model for the flame thrower) wrote the Flexner Report, which served as a basis for curriculum reform for medical schools in the 1800s, and happens to be a report with which Jim is familiar.

At Flexner’s studio in New York, Jim and Joe met a number of French artists. They became friendly with Edouard Prulhiere when he lived in New York, painting and working as a gallery assistant to Julian Schnabel. And they became acquainted with many of the French artists who showed with Flexner and Prulhiere in Paris at Galerie Meteo. Several years later, Jim and Joe visited the Flexners in Nice, a summer visit they have repeated over the years. They often spent time there visiting other artists studios. During their stays, they become more familiar with the School of Nice, a loosely defined “school” of three generations of artists, beginning with Yves Klein and including in its second generation Noel Dolla, Daniel Dezeuze and Flexner. Through Dolla, Jim and Joe met and collected work by two of his students, Dominique Figarella and Philippe Mayaux.

During a studio visit with Flexner and Jim, I pointed out that Flexner’s work, with its flat space and rich but thinly applied paint, was incongruous with much of the other work in the Cottrell-Lovett collection, which is defined by tactile, textured surfaces, bright and aggressively blended colors and abstract imagery. But as Flexner countered, “Jim, like everybody else, has contradictory approaches. I often notice he likes the medium and the material. He’s attracted to relief and texture. What I do is extremely thin and flat and he likes that, too.”

Flexner does not differentiate between figuration and abstraction in his work. For example, he sees Untitled (blue room with curving line) (1987), with its minimalist/color field sensibility, as similar to Untitled (people with torches) (1986). Though Flexner does not necessarily view his work as narrative, the two works do document an “event.” Untitled (people with torches) was not made to tell a specific story but over the years Flexner realized it could relate to his memories of religious processions in France, while the “event” in Untitled (blue room with curving line) is more subtle, relating to the way paint is applied, how light reflects in a painting and how a simple, improvised line is made with a single gesture.

“It is an ‘event’ in the sense of Chinese calligraphy,” explains Flexner. “Doing something in one breath. You start a line and end up when the breath is finished.” (It’s interesting to note that Flexner’s bubble drawings, made with soap, glycerine and India ink, are also the result of a single, extended breath.)

Not all of the connections made through Flexner were with the French community. For many years, Flexner and Malcolm Morley lived in the same apartment building on Spring Street in New York City, and Flexner introduced Morley to Jim and Joe. Their first purchase of Morley’s work was a small watercolor, Untitled (n.d.), and they have since acquired, in addition to the painting Santa Maria with Sopwith Camel Wing (1996), Still Life with Two Planes (2000-2002) and A Hun Burst into Flames and Another Came Spinning Eastward (1992). Coincidentally, the later work is a watercolor study for the large Morley painting, Dawn Patrol (1992), in the Orlando Museum of Art’s permanent collection.

When Jim saw the paintings of Miguel Barcelo exhibited at Leo Castelli Gallery in 1987, he responded immediately. After discussing the work with Flexner, who was equally enthusiastic, he purchased In Vitro (1987) from the exhibition. Jim was fascinated by Barcelo’s expressive process, his use of organic material and imagery abstracted from nature. It comes as no surprise that Jim eventually met Barcelo and bought more of his work.

During a visit to Barcelo’s studio several years later, Jim saw four large-scale paintings that had been commissioned by the contemporary art museum in Barcelona. He loved the work, but all four paintings were spoken for. However, several months later, Barcelo called him to say the museum only wanted two of the four. Was Jim interested in purchasing the other two? That is how Soupe d’Ane (1997), a major Barcelo work, came into the Cottrell-Lovett collection.

Even as his relationships with artists develop, Jim won’t let a friendship or acquaintance override his decision to acquire or not acquire a work. Flexner’s Untitled (blue room with curving line) (1987) is a prime example of this philosophy. “I’d seen the work a lot and I wasn’t interested. But Joe really loved it and encouraged me to take a second look. The more I looked, the more I saw the contrast between the two paintings (people with torches and blue room with curving line). Though they evoked different emotions and different feelings, I began to see them as a pair.”

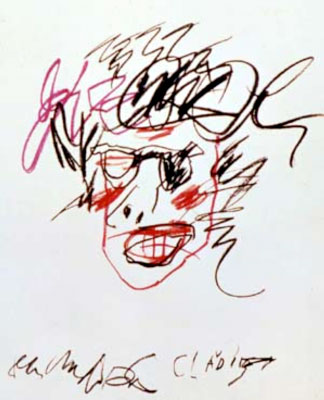

In the early 1980s, Jim met a young, relatively unknown artist named Jean-Michel Basquiat and subsequently bought his work, which he loved for its spontaneity. Though many of Jim’s friends questioned his sanity for buying Basquiat in those early days, it is a testament to his insight that these works have grown in importance. Jim believes there is a message in the work that is accessible to everyone. During one of their conversations, Basquiat told Jim that The Three Deligates (1982), with its brown, gold and white faces, came from the artist’s memories of visiting the United Nations as a young child. Years later, Untitled (1994), by Todd Murphy, was acquired. Many of the qualities in this work — a raw expressiveness and a graffiti-like delivery — that attracted Jim early on to Basquiat still speak to the collector today.

The relationship between collector and artist can be symbiotic give-and-take. Such is the case with Suzanne McClelland, whose scope of work in the Cottrell-Lovett collection spans a decade. McClelland often deals with language in her work, collecting words by listening and translating this sound and speech into visual form. The physicality of speech can be displayed in paint because paint is so flexible and malleable. And because speech comes from the brain faster than written language, abstraction is the perfect vehicle for found speech. Mystery hidden meaning and varied interpretations — all qualities that can be found in much of the work in this collection — are attributes of art that appeal to both Jim and Joe. As McClelland notes, “Collecting spoken words is a subjective process. Collecting art is, too.”

Collecting McClelland’s work is an indication of Jim and Joe’s ongoing curiousity about art and their willingness to buy work that is not transparent. “The personal nature of Suzanne’s work is not clear to me as yet,” Jim wrote recently, “but as I know more of her, I’m sure it will become that way.”

When I asked McClelland what it meant to an artist to have the ongoing support of specific collectors, she replied:

The real collector, the kind who collects in depth and spends time with the work, has an eye that interests me. Making work is something that artists do regardless of the collector. But an artwork has a new life when it finds a home with people who follow a particular artist and put it into a context with other artists who may also reflect their thoughts and taste. It gives it a specific place in history. If I were to keep paintings to myself it could be suffocating, like home schooling — isolating and self-protective. I like to lose control of the work through somebody else’s eye, and some of my paintings have been fortunate enough to end up with Jim and Joe.

Deborah Kass met Jim and Joe through mutual friends. A rocky start caused by reciprocal dislike of one another’s dog transformed into a close friendship and eventually into a collector/artist relationship. ” I love people like Jim and Joe who want to get into my brain, to that extent,” Kass says. “That and a curator or writer doing the same are things any artist wants.”

Over the years, Jim and Joe have bought excellent examples from each of Kass’ series. They own particularly strong examples from her art history series as, How Do I Look? (1991), which references Picasso; Call of the Wild (for Pat Steir) (1989), which quotes from Steir and uses the abstract marks of Lee Krasner; and Short Stories (1989), a transitional work that led to the art history painting series. “Jim and Joe own some of my best work,” Kass says, “and I feel it’s safe with them, in every way.”

“The historical references in Debbie’s work made me pay more attention to contemporary painters,” says Joe. “I don’t know painters that well except for French artists. Her work made me look and think about contemporary art more.”

David Hockney is a bit of a wild card whose work came into the collection when two of Jim and Joe’s friends, Mark Berger (a schoolmate of Hockney’s in London) and Nathan Kolodner (whom Jim met at the gym), introduced them to the artist and his work. The collection contains an important early painting from 1964, Untitled (Landscape #1 and #2), and a large grouping of drawings used as studies for later paintings. “We liked Hockney’s early imagery, or lack thereof — images that suggest there’s more to come,” Jim says. “His work has hidden meanings and yet is personal.”

Jim met Jonathan Lasker more than a decade ago, when Lasker had his first opening at Sperone Westwater Gallery in New York. Though Jim and Joe are friendly with many artists, they also have close relationships with dealers such as David Leiber, a partner at Sperone Westwater, who introduced them to Lasker. Though Jim did not initially respond to the work, he came to appreciate the tactile quality of Lasker’s paint application and purchased Improved Expressions (1991), from this first show. Later, he bought Symbolic Farming (2001), a painting he was attracted to not only for its beautiful surfaces and abstract markings, but also because it conjured up memories of his childhood in the farmland of West Virginia. (This sense of association triggered through memory or conceptual connection is another important but less obvious component of Jim and Joe’s selection process. For instance, At the Drive-In (ca. 1955), by O. Winston Link, is a photograph of a drive-in Jim frequented as a teenager in West Virginia.)

“I have a body of work that spans about 25 years,” Lasker says, “and I do like it if people collect from different periods. It shows an engagement and dialogue with the work. I like what Jim and Joe collect. They have a strong sensibility, particularly in regard to painting. It helps if your work hangs with other artists who you feel an engagement with. It means there is a sensitivity.”

Taking a collection out of a domestic situation and hanging it together on the walls of a museum is a true test of whether this sensitivity exists or not. The eye and intent of the collector is revealed. We can only imagine what will happen with the Cottrell-Lovett collection when it returns home. Years ago, when I was working on an exhibition with Alex Katz, he told me his retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art triggered his own reassessment of his work. Many artists, I think, have that response. I believe we’re seeing the Cottrell-Lovett collection at its mid-point, and that it will continue to grow and deepen. Neither Joe nor Jim has any plans to quit collecting. In fact, quite the contrary, they recently acquired a large drawing by Jorge Queiroz, a young Portuguese artist about whom they knew nothing. But when they saw his work at Galerie Nathalie Obadia in Paris, they simply had to have it.

Collecting continues to be an obsession. And how can it be otherwise? “When I see a painting I really love, the image stays in my mind, it persists,” Jim explains. “Whether I buy it or not, it haunts me.”

This essay is included in the Orlando Museum of Art’s exhibition catalogue — Co-Conspirators: Artist and Collector, The Collection of James Cottrell and Joseph Lovett (2004).