Independent and International

Highlights of the Cottrell-Lovett Collection

By Raphael Rubinstein

Since I first met James Cottrell and Joe Lovett, about 10 years ago, I have been a great admirer of their art collection. A large part of this admiration has to do with aesthetic affinity: their collection includes many of my favorite artists, figures whom I’ve written about repeatedly. But equally important, for me, is the independence of their choices. One of the most unfortunate aspects of the booming art market of the last few decades has been the herd mentality that seems to drive most American collectors. Nearly every one of them seems to want exactly the same artists, which not only drives up prices (good for a few artists and dealers, I suppose), but also results in the same collection being cloned throughout the country. (I’m putting the stress on American collectors because this tendency seems much more pronounced here than in, say, Europe, where collections tend to be more individualistic.) Whatever the causes of this development, it seems to me not a good thing for the health of contemporary art or for culture in general.

It’s safe to say that there is no collection of contemporary art in the United States like this one. Although Cottrell and Lovett have sought out works by some of the most celebrated artists of the last 20 years — figures such as Jean-Michel Basquiat, David Hockney and Robert Mapplethorpe — they have also explored areas of artistic creation that few, if any, other American collectors know exist. I’m thinking in particular of the contemporary French artists (Noel Dolla, Roland Flexner, Daniel Dezeuze and others) who have such a prominent presence in the Cottrell-Lovett collection. Clearly, this is an assembly of art that follows the sensibilities of two individuals and not any critical orthodoxy or fashionable shopping list, which is what makes it so rewarding to look at and to think about. May its independent character be an inspiration to other art lovers.

Herewith, then, is some commentary on highlights on the collection.

The 1980s were marked by a return to painting. This revival, which came after a period in which conceptual and performance art seemed to dominate, was widespread, occurring throughout Europe, Latin America and the United States. It was especially strong in New York, where in the early part of the decade it was often closely involved with the burgeoning hip-hop culture and the artistic ferment of downtown Manhattan. Included in the Cottrell-Lovett collection are works by three artists who drew inspiration from, and significantly contributed to, this milieu: Jean-Michel Basquiat, Keith Haring and Donald Baechler.

Basquiat’s Three Delegates (1982) dates from the period that Richard Marshall identifies as the earliest phase of the artist’s career. “From 1980 to late 1982,” says Marshall, who curated the 1992 Basquiat retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art, “Basquiat used painterly gestures on canvases, most often depicting skeletal figures and masklike faces that signal his obsession with mortality, and imagery derived from his street existence, such as automobiles, buildings, police, children’s sidewalk games and graffiti.” In this painting, which combines acrylic, oil stick and collage, the trio of faces and surrounding calligraphic marks reflects two of Basquiat’s biggest influences, Jean Dubuffet and Cy Twombly. What is especially striking about this painting, however, is the absence of text (the collection’s other Basquiat, from two years later, Untitled, 1984, displays the artist’s poetic use of found writing). It’s one of the relatively few Basquiats from this period, which poet Rene Ricard characterized as “the happiest time” of the artist’s life, which relies almost exclusively on pictorial means to convey its vision of urban pressure and anguished, totemic visages.

Keith Haring, a close friend of Basquiat’s who similarly first gained fame as a graffiti artist, is represented by a rare early work. This nearly 10-foot-high untitled work dates from 1978, the year that Haring came to New York from Pennsylvania as a scholarship student at the School of Visual Arts (SVA). It was at SVA that year that Haring developed his distinctive style. As he later recalled, “I bought a roll of oak-tag paper and cut it up and put it all over the floor and worked on this whole group of drawings. The first few were abstracts, but then these images started coming. They were humans and animals in different combinations. Then flying saucers were zapping the humans. I remember trying to figure out where this stuff came from, but I have no idea. It just grew into this group of drawings.” What’s exciting about this work is that one can see Haring in these rhythmic sequences of dashes, dots and curves, on the verge of discovering the pictographic vocabulary that would soon be disseminated around the world.

While Haring was at SVA, a dozen blocks away another young painter, Donald Baechler, was studying at Cooper Union. Although he initially showed at the same gallery (Tony Shafrazi Gallery) as Haring and favored a raw, intentionally primitive figuration, Baechler’s work is far more involved in traditional painterly issues. Often using found figure drawings, he juxtaposes objects and figures according to an oblique but graphically potent logic, as seen in the untitled 1988 painting in the Cottrell-Lovett collection. In a 2000 interview in Bomb magazine, Baechler spoke about the subjects of his work. “I think that, for me, the head is always a kind of surrogate for a self portrait, and the flowers almost a replacement for the human figure in the painting. I’ve made an almost intentional point of not studying botany or not learning what these flowers are that I’m drawing. I buy flowers at the Korean deli on the corner, but you know, I can barely distinguish between a tulip and a rose, which sounds stupid, but it’s true. For me a flower has this very convenient, almost human dimension, with the head and the stem and the leaves replacing certain body parts.” Another work in the collection, Flower #1 (1993), shows the result of Baechler’s surrogate figuration and his economical graphic sense.

Although his work veers more toward abstraction and he has spent large parts of his career outside the U.S. (mostly France), painter James Brown was, for a time, part of the same New York scene as Basquiat, Haring and Baechler. His work of the early 1980s uses a raw, totemic figuration (influenced by Jean Dubuffet and African art) that has affinities with Basquiat’s work. But running through Brown’s oeuvre is a strong religious feeling, one that shows influence of his Catholic education. (He received his BFA from Immaculate Heart College in Hollywood.) This aspect of his work is confirmed by an oil and zinc on panel painting titled Stabat Mater Yellow VI (1989). The painting, which shows a pair of thin totemic forms against a metallic gold ground, belongs to a large series of works inspired by Giovanni Battista Pergolesi’s famous 1736 musical setting of the Stabat Mater Doloroso hymn, which offers compassion for the mother of Christ at the Crucifixion. One commentator on Brown — French poet and critic Jean Fremon — tells us that the title of the series is connected to the artist’s habit of listening to the same piece of music again and again as he works on a series of paintings.

Other works in this collection give a sense of how widespread the revival of figurative painting was in the 1980s. Mexican-American painter Ray Smith, who began showing in the mid-1980s, combines allusions to European high-modernism with the vernacular Mexican imagery and the disjunctive visual syntax of David Salle and Julian Schnabel. His large four-panel oil and wax on wood painting Erotica, Neurotica (1989), uses motifs from Ferdinand Leger behind sparring animals. In Europe, this figurative painting revival was first felt in Germany and Italy but soon spread to other countries where, encountering specific cultural traditions and conditions and the unique sensibilities of individual artists, it took on a variety of forms. In Spain, the most prominent of the new figurative painters was Miguel Barcelo, an internationally known artist who divided his time between Paris, the island of Mallorca (where he was born) and the West African nation of Mali, whose Dogon culture has been a major influence on his work since 1988. Cuisine is one of the recurring themes in Barcelo’s highly tactile and densely composed paintings; books are another. Both are present in the large, densely painted canvas Soupe d’Ane (1992). The French title which translates as “Donkey Soup,” allows us to identify the legs sticking out of the huge oval cauldron that fills nearly all of this giant painting. Most of the other ingredients aren’t so easy to identify, though onions, turnips and shellfish seem to be present. Most unusually, there appears to be an open book near the upper center of the painting. One can make out some upside down letters on its spine that spell out “todo,” Spanish for “everything,” which might well be the recipe for this dish. For Barcelo, soup has metaphorical meaning. Speaking of paintings like Soupe d’Ane, he once said, “The soup represents a little bit the image of cultural chaos; it is the last image to create when nothing else is possible.” In such works, he says, he wants “to show painting for what it is, its wealth and its misery.”

In France, a movement coalesced in 1981 around the banner of “Figuration Libre” (Free Figuration). The two Figuaration Libre works in the collection, Robert Combas’ painting Autoportrait en cuiseur d’oeuf (Self-Portrait as Egg Cooker) (1981) and Jean-Charles Blais’ gouche Untitled (1984), suggest the scope of the movement, which included comic-book influenced artists such as Combas and more traditional Neo-Expressionist painters such as Blais. Complicating Blais’ expressionist style, however, was his practice of appropriating images from other artists, mostly the early 20th-century modernists, and pushing his work toward abstraction. Speaking in 1984, the year of this work, he said, “I paint figures which are no longer people but objects … The body has become a piece of painting.” Combas’ work, by contrast, is brashly populist, borrowing enthusiastically from comic books, art brut and hand-painted advertisements, stirring in sexuality, violence and satiric scenes of everyday life (as in Autoportrait en cuiseur d’oeuf). Stressing his working-class background, Combas says that in the beginning his style was “a derisive reaction against the intellectual painters of the 1970s.” It’s important to keep in mind, however, that Combas’ embrace of a comic-strip style of figuration reflects the relatively high esteem that the French cartoonists or bande dessinee have long enjoyed in France.

Although Combas doesn’t name names, I suspect that those “intellectual painters of the 1970s” included participants in the Supports/Surfaces movement. It is another mark of this collection’s openness that it can accommodate Figuration Libre painters and two of the leading Supports/Surfaces artists: Daniel Dezeuze and Noel Dolla. Launched in the late 1960s, Supports/Surfaces focused on the components (physical and ideological) of abstraction. In parallel to Postmodernism in the U.S. and Arte Povera in Italy, Supports/Surfaces sought to break existing boundaries, whether through the use of unstretched canvas, outdoor exhibitions or Marxist analysis, while maintaining a strong retinal and tactile component and references to the modernist grid. Dezeuze, represented here by Untitled (1984), a chalk on paper drawing, is a multifaceted, often allusive artist. His best-know works include large, flexible wood lattices. Sometimes painted, sometimes not, they are exhibited both rolled and unrolled, existing somewhere between painting and sculpture. His work often touches on topology and oblique representation.

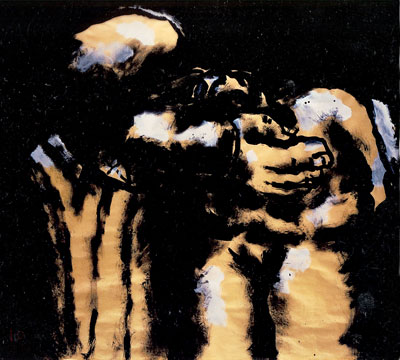

Dolla is even more varied than Dezeuze in his artistic practice. Since the late 1960s, he has continually sought out new approaches to painting, submitting the medium to his restless imagination and intellect. This has meant everything from abstractions created on handkerchiefs and dish towels, to three giant dots painted temporarily in the sand of a beach in Nice. In the mid-1980s, Dolla created the “Tchernobyl” series, which includes the three-panel painting illustrated in the catalogue. When these works, which feature primitive figures and roughly textured surfaces, were first shown in public, some accused Dolla, whose previous work had been exclusively abstract, of jumping on the Neo-Expressionist bandwagon. Only later did Dolla reveal that he had made the paintings with one eye covered and one hand (the one he normally favors) tied behind his back. The paintings were at once Dolla’s critique of what he saw as the regressive tendencies of Neo-Expressionism and the protest against the then-recent nuclear disaster in Chernobyl.

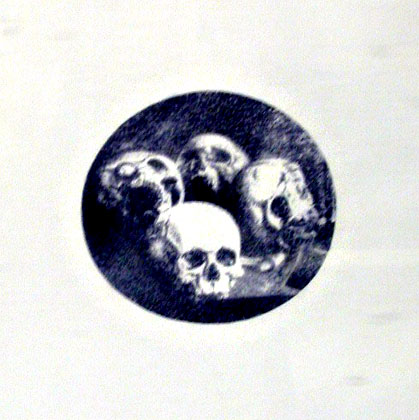

Another important figure in recent French art, Roland Flexner, is well represented in the Cottrell-Lovett collection. Born in Nice, Flexner has been living in New York for the last 20 years, where he has developed a unique body of work that combines meticulous execution and emotional power. A pair of large canvases from 1987 — Untitled (people with torches) and Untitled (blue room with curving line) — exemplify Flexner’s approach to painting: instantly memorable images; a smooth almost impersonal facture; compositions that stress the contours of the forms; and a certain withholding of meaning. Are these luminous torch wielders a threatening mob or a celebratory crowd? Is this schematic blue room an abstraction veering toward representation or vice versa? The paintings also show Flexner’s penchant for technical experimentation. Untitled (people with torches) is gilded, which means the paint has been laid down over a tin surface, while Untitled (blue room with curving line) uses a gilding technique for the line of the title and oil and wax for the rest of this cool monochrome. The 1993 graphite drawing Untitled (cluster of skulls) belongs to a series of precisely rendered small-scale drawings, many of which utilize similar momento mori imagery. The “bubble drawings” are prime examples of Flexner’s ongoing series of works made with soap and India ink bubbles, which the artist blows and then causes to burst onto sheets of paper. The range of effects in these unconventionally made, incredibly detailed drawings is amazing. They can evoke landscapes, swirling rivers, underground strata, celestial bodies of microscopic life forms. As I observed in an article on Flexner published last year in Art in America, the bubble drawings “offer miniature subtleties of shape and line that no human hand could ever achieve, and a degree of complexity that even computers might find unattainable. There’s not a single pinprick-sized area of the drawings that doesn’t offer something to look at.”

Also present in the collection are three of the best younger French artists: Dominique Figarella, Philippe Mayaux and Edouard Prulhiere. In the work of Figarella, who was a student and assistant of Dolla’s before launching his own career, the process of making the painting becomes inseparable from the final result. In an early work from 1993, the artist uses wide bandages to hold the pink and green paint in place. On the one hand the bandages encourage a metaphorical reading — painting is in a wounded state, the artist must heal it — and on the other, they establish a subtly warping grid and give the painting a simultaneous sense of thickness and transparency. In a more recent work, Repaint? (2002), the paint is contained by the rubber tips of five toilet plungers compressed underneath a sheet of clear Lexan®. As usual with Figarella, the work conveys a sense of formal tension and irreverent, do-it-yourself ingenuity. Prulhiere, who lived in New York for a number of years but recently returned to France, takes a similarly irreverent stance toward painting. In Waiting for the Elevator (2003), several vividly colored canvases seem to have been taken off their stretchers and roughly reassembled to create a painting-sculpture hybrid that is at once violent and tender. Mayaux calls on a very different tradition: the mocking, visually paradoxical Surrealism of Rene Magritte, mixed with Marcel Duchamp’s pun-laden erotics. A master of faux-anonymous representational style, Mayaux often loads his paintings with outrageous sexual-puns.

The collection also includes some of New York’s strongest painters: Jonathan Lasker, Suzanne McClelland, Amy Sillman and Deborah Kass, each of whom has developed a wholly individual response to the achievements of mid 20th-century modernism. Lasker’s bold, thought-inducing paintings, which are careful enlargements of small sketches, reinvent gesture as a decorative element and a philosophical conundrum. McClelland also finds new ways to work with gestural painting, using eccentrically formed letters as a kind of trellis for her densely layered, fanciful yet tough-minded abstractions. More lyrical than Lasker or McClelland, but also willing to follow her rich visual imagination into cartoony imagery. Sillman fruitfully explores the zone between figuration and abstraction that attracts so many artists in this collection. For her part, Kass takes a more critical view of the modernist heritage, juxtaposing classic images (Pablo Picasso’s Portrait of Gertrude Stein and Jasper John’s The Critic Laughs and hijacking others’ styles (her Warholian painting of Barbra Streisand) to perpetuate acts of cultural subversion, as well as make some gorgeous paintings.

British-born, New York-based Malcolm Morley is represented by two important paintings that combine nautical and aerial imagery. After doing poineering work as a Photorealist and a Neo-Expressionist (avant la lettre), Morley began making paintings that feature exquisitely rendered ships and planes. Many of these works are closely connected to a traumatic childhood memory that the artist only recently recovered through psychoanalysis. Living in London during World War II, his family was several times forced to leave their homes by German bombing. In one instance, the young Morley had placed a recently completed, much-beloved model ship on the windowsill. That night the shock wave from a VI rocket attack dislodged and destroyed the balsa-wood model, a loss that became emblematic of all the dislocations Morley suffered as a youth. In these recent works, which feature many surprising details (such as the trompe l’oeil frame in Santa Maria with Sopwith Camel Wing (1996), Morley has transmuted this piece of autobiography into audacious, virtuosic paintings.

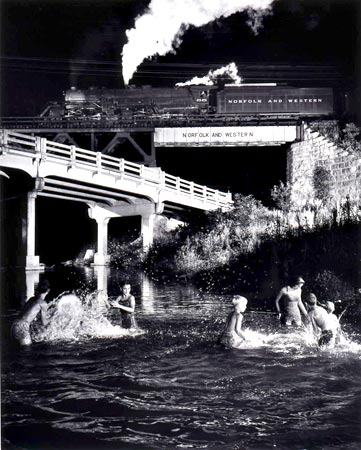

Another American-loving Brit, David Hockney, is represented by several early works, including Untitled (Landscape #1 and #2), which, like Morley’s Santa Maria with Sopwith Camel Wing, has a painted border — in this case, representing two window frames. The year this diptych was painted, 1964, was important for Hockney on at least two counts: he moved to Los Angeles (after a semester teaching at the University of Iowa) and switched from using oil to acrylic paint. As critic Marco Livingston points out, the matte surface of Hockney’s acrylic work is related to the “flat anonymous surfaces of photographs.” In his monograph on Hockney, Livingston also tells us that in 1964 the artist acquired his first Polaroid camera. (Interestingly, the O. Winston Link train photographs from the 1950s in this collection have spatial anomalies not unlike some of Hockney’s mid-1960s canvases.) Stylistcally close to both Hockney’s Iowa paintings and his first Los Angeles canvases, this diptych features a simplified mountainous landscape that one might surmise Hockney encountered while traveling from Midwest to California.

The international flavor of this collection is echoed in one of the most recent additions to it: Barton Lidice Benes’ Souvenirs (2003). A New York-based artist whose work frequently involves treating bits of pop-culture ephemera like holy relics, Benes operates in a self-invented aesthetic zone that overlaps with Joseph Cornell, the wunderkammer tradition and Andy Warhol’s “time capsule” boxes. For Souvenirs, he used paper currency to fashion 72 tiny objects, each of which is representative of a different country: a wooden shoe for Holland, a steak for Argentina, what seems to be a detail of a Charles Rennie Macintosh window for Scotland, and so forth. Mounted as a grid in a box and individually labeled, these charms are miracles of craft and a witty commentary on the tyranny of national characteristics and the circulation of money. More somber is Benes’ Combination Therapy (1993), a mosaic of a human skull made not from ceramic tiles but from AIDS drugs (specifically the pills used before the advent of the “cocktail”). Evoking a Mexican Dia de los Muertos celebration and once again displaying Benes’ ingenuity, the piece is at once a rueful acknowledgement of death and a symbol of art’s potential for triumph.

This essay is included in the Orlando Museum of Art’s exhibition catalogue — Co-Conspirators: Artist and Collector, The Collection of James Cottrell and Joseph Lovett (2004).